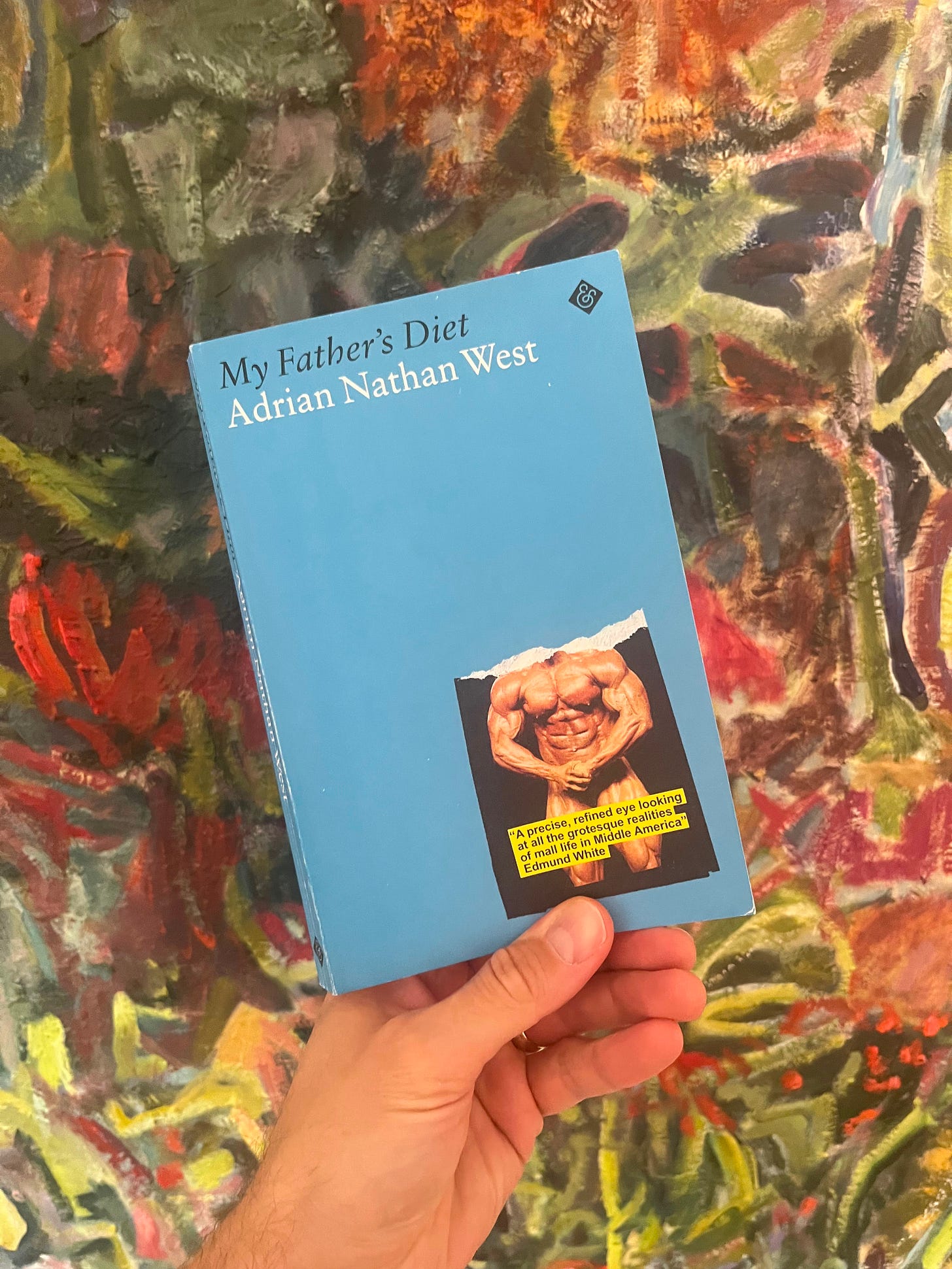

The Magic of Masculinity

Thoughts on Adrian Nathan West's "My Father's Diet" and the final word on masculinity.

My Father’s Diet quietly captures the innate ambitions of middling masculinity. In West’s novel, the men, who are ultimately corrupted by desire, act in hope of dispelling the feelings that come from desire when it is left unrealized—which is most of the time.

The narrator is a child of divorce—unmotivated and seemingly depressed—who is now in college (and mostly failing) in a small city in middle America. Here he is in French class (his major):

I could not answer, not only because I had no justification for not fearing dogs, but because I couldn't recall the subjunctive for any of the verbs that seemed pertinent to my reply.

I tried to prevaricate with, "Les chiens sont sympathiques." My professor explained for a second time the rationale behind the exercise and the form our answers should take, in French and briefly in English: "J'ai peur que les chiens me mordent" I am afraid dogs might bite me. She posed me the question again, and I managed, with my mangled pronunciation, to say, "Jaime bien les chiens." She explained the procedure again, with what I am sure she considered patience but what for me was a misplaced faith in the pedagogical utility of humiliation. I looked away, opening my hands in bewilderment, first at my activity partner to my left, then at the grainy plastic surface of the desk, covered with profanities in graphite and clues to exams past, until, after fifteen seconds of silent shame, she moved on to someone else.

I will re-direct your attention to a line like “a misplaced faith in the pedagogical utility of humiliation” and, your word of the day, prevaricate.

The main thrust of the novel comes when the narrator’s father re-enters his life. The narrator observes—and at times tags along at his father’s insistence—his father’s life as it crashes and burns through a new marriage, a sputtering wellness clinic, and, eventually, an amateur body-building competition.

On paper, one could say the narrator’s father comes up short, in what amounts to a comedy of errors (one scene involving an RV and a skunk comes to mind). However, it isn’t all comedy nor all errors. As the narrator’s father begins his bodybuilding journey:

Although my father had, just after mailing his entry form, gone to Vitamin Warehouse and bought several weeks’ worth of whey and egg protein, creatine monohydrate, HMB, glutamine, and shark cartilage, the pressures in his life proved stronger than the inspiration the video afforded. He found it shameful for an adult to rent, particularly in an apartment complex, and he looked forward to buying a new home as soon as possible; but when he sought preapproval from a mortgage broker, his credit check revealed that Karen had taken out a number of high-interest loans without his knowledge. Several were already delinquent, and any future loans were contingent on their payment in full. He was disappointed, but not bitter. He still loved her, and talked occasionally over dinner about how deep their friendship had been, about the beauty of her eyes, and about the tender and humorous moments that had passed between them.

The fact is, the father never fails to show up. He works more than ever to financially support those around him while almost always nagging his ambivalent son into joining him for dinner or to hit the gym or on a family road trip. What’s compelling about the father character is how often he puts himself out there—trying new things, dating again, calling his son for advice or just to gripe. It’s a refreshing picture of masculinity that doesn’t immediately spring to mind when one hears the word, even though West’s portrayal is far more realistic and true to life than the tailored or twisted versions of men we experience through culture (the influencer, the optimized tech bro, the perennial star athlete, etc.).

The strength of West’s hand is subtle and yet his prose is undeniable. While the plot quietly advances, it’s the writer’s expertise doing the heavy lifting. I dog-eared many pages, and have decided to include some particularly shining examples that arise when the narrator encounters Fox, his on-again, off-again:

Fox: I associate her name with certain casts of sky, in particular a blue-black one with whitish tufts of cloud poking out like puffs of piling from a threadbare sofa. Not from the day we met, of which I remember little but the sight of her in three-quarter profile, eye makeup in filigree extending almost to her ear, and then my initial, for me unusually bold, approach to her to ask for a cigarette, and her mocking laughter through gapped teeth as I lit it, on account of my liking the Rollins Band, whose name was printed on my shirt. The sky in question is from a night sometime later, two or three weeks before we slept together, when she still had a boyfriend, a bantamweight rockabilly type with a large, almost oblong head that was resistant, unlike my own, to the incursions of pattern hair loss. I met her out —she had invited me when I ran into her in the student center, and I hoped, since her remarks about her boyfriend were unflattering, that she would decide to spend the night with me.

And, later on, after a prolonged break up:

I stayed with her for two more nights: happy ones, in essence, and we spoke tentatively of my returning there to live with her.

It was not so much a lack of love as a lack of imagination that made me refuse; failing to grasp why I'd been so miserable before, I was unable to see how I might live with her in another way. My return bus left at eight on Monday morning; I set the alarm on my watch for six. She barely woke when I kissed her goodbye, her words and the way she hugged me still had about them the volatility of dreams. I walked to the bus station alone. At the diner across the street, I ordered a coffee to go, and stood drinking it a while at the counter, looking up words from Germinal.

What also feels true in this book is the care for one another the men indirectly express—again, this idea of showing up—as the narrator and his father make time for each other, but not in an Hallmark, strings-rising, running-in-the-street, slow-clap kind of way, no, this book is far more subtle, in the same way that life is subtle. The characters live in the orbit of their jobs, relationships, and family, and even though the narrator himself floats around, already checked out, the small pull of gravity from his father’s life cannot be escaped.

At one point, father and son attend an amateur body-building competition as members of the audience:

As the finish grew closer, and the possibility of gaining more muscle or losing more fat diminished, my father took a greater interest in the aesthetics of the sport, and thought he might learn something about posing technique that would make his photos stand out from the others.

During the car ride there:

He apologized again for his absence in my childhood, for having thought about himself when he should have thought of me.

“It’s fine,” I told him, unable to arrive at a more comprehensive or sympathetic response.

And really it goes without saying, because it is obviously fine, as the two of them have, at this point, spent the better part of the book (their recent lives) together, sharing meals and conversations, making up for lost time.

Once more, as they leave the competition:

“So what did you think?” he asked, once we’d turned onto the main road.

“It was something different,” I said.

“Yeah, that’s for sure. Kind of weird, right?”

“They all looked like they’d been cooked in one of those spinning hot dog ovens,” I said.

My father laughed, and we drove the rest of the way in silence.

I wanted to use West’s book and my experience with it as a vehicle to sort out some seemingly complex thoughts I’ve had for some time regarding masculinity and, simply, or not so simply put, the idea of it, its nebulousness, the danger, ultimately, everyone else’s idea of it—your idea of it, I suppose, but I haven’t quite got it. Perhaps it’s far too complex than I thought, though my gut tells me that it isn’t, that maybe it’s just not worth the words. The more we talk about masculinity, the more I think about it, the less specific it becomes, the less it means. It can be weaponized, it can be celebrated—and there is magic in that.

All I really want to say to you is the idea of masculinity (if we are going to be forever forced to distort it into the lens that it isn’t, forced to reconcile with it as an invisible stain that can’t be scrubbed out) is that masculinity, for all its weapons, for all its feats, is only what you make it, and it’s for everyone, so do with it as you please, your best, your worst.

In My Father’s Diet, Adrian Nathan West captures the magic of masculinity, which in my case, is a real, accurate, poetic portrayal of men—men in the middle of their lives (not temporally, so much, but in the middle of moments, in the middle of their next chapter, the next relationship, or stuck in the middle of the one from before). They are in the middle but not stunted, creating a kind of average, where average is normal, and normal, in our current time—doused in accelerant—is special. In the grand scheme of things, as I furtively look through the lens of masculinity, as I stare at its stains, this book is a small story, but a remarkable one, and similar to most men I know, far more worthwhile than you might think.

Great review. I’ll have to read this book. If you have any interest in wrestling with masculinity in your own fiction, @Bad Clown Books has the anthology for you. We’d love to read any submissions you might have.

I said in a comment somewhere I was gonna read this book, but now, after reading the excerpts, I really mean it! That writing is superb. Also, knowing you're a Jordan Castro fan, you're gonna love his new book "Muscle Man."